Environmental Protection Market in China

Last update: November 2022

After 20 years of full steam development, China entered the new millennium with such an amount of pollution to rise an ever growing social alarm and concern, due to its impact on people health, pushed also by such a severe air pollution that, in many major cities, the sky was screened by a permanent layer of smog for most part of the year.

During the 11th Five Year Plan (2005 - 2010), the Communist Party of China (CPC) understood the importance of setting a new course, introducing a new radical vision incorporating environmental protection into the concept of development, under the name of "Ecological Civilization".

The turning point is the 12th Five Year Plan (2011 – 2015), laid down by President Hu Jintao and inherited by President Xi Jinping, with an impressive amount of structural reforms:

- Air Pollution Action Plan (2013)

- New Environmental Protection Law (January 2015)

- Water Pollution Action Plan (March 2015)

- Reform of Concessions and Public Utilities, with opening to Public-Private Partnership (June 2015)

- Integrated Reform Plan for Promoting Ecological Progress (September 2015)

- Guidelines for issuance of Green Bonds (December 2015, People Bank of China and NDRC)

This set of structural reforms were intended to tackle environmental pollution and enforce ecological protection with a pincer movement, by rising a way more stringent regulation and setting market mechanisms, in order to transform environmental protection into a business opportunity, actively involve the population and the companies and attract both industrial and financial private investors.

In 2015, the Green Finance Committee of People Bank of China, clearly stated[1] that, to face the huge amount of expected investments for environmental protection and green transition (at least an annual investment of 2trillion RMB - 320billion USD), public funds could only contribute 10% to 15% of the required financial need: the private sector was expected to be the largest source of capital, contributing 85% to 90%.

Three are the pillars of the overall reform:

- pushing companies to invest in environmental protection compliance, including decarbonisation,

- opening Environmental Protection to private investors through Public-Private-Partnership and establishing market mechanisms,

- establishing a financial leverage through the emission of Green Bonds

The 13th Five Year Plan was expected to favour the booming of the environmental protection market, led by a wave of investments, but the results didn’t achieve the expected results.

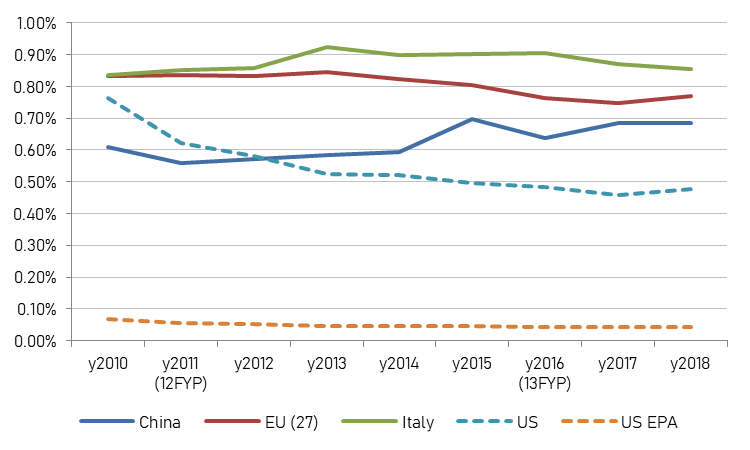

The Chinese Government Expenditure on Environmental Protection on percentage of GDP clearly achieved its peak during the 12th FYP, growing closer to the values of the European Union, but wavered during the 13th FYP (Figure 1).

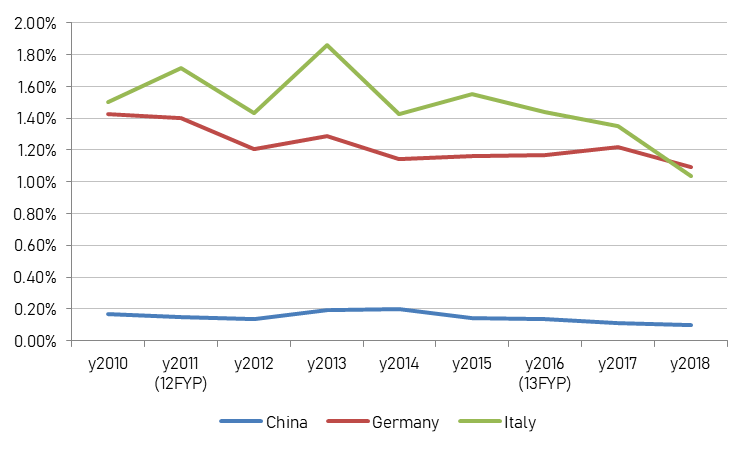

Also the Investments completed in treatment of industrial pollution on percentage of total industrial investments achieved its peak in the middle of the 12th FYP, but then it decreased below the level at the end of the 11th FYP, with values 10 times lower than those of Germany and Italy (Figure 2).

At the end of the 12th FYP, the Chinese Government, well aware of the complexity that a continent-size Country requires for a comprehensive ecological and environmental protection, was in need to establish a Governance mechanism that was worthy of the challenge.

The 13th Five Year Plan focused on tightening the regulation and in reforming the administrative processes as a comprehensive mechanism under the guidance of the Government and the “Command & Control” policy, in a delicate process to push the local Governments in adhering to the national model without prejudice of the local autonomies, while the market mechanisms were left as defined during the 12th FYP.

As a matter of fact, the environmental protection market lost its momentum, mainly for two reasons:

- the reform of the Public Concessions and Public-Private-Partnership didn’t work as expected

- the green bonds matches a tepid demand and, not being aligned to international definitions (such as Climate Bonds Initiative), the Chinese green bonds ended up to support projects related to coal and fossil fuel exploitation.

The 2015 Reform of the Public-Private-Partnership opened to the private sector the possibility to invest in environmental facilities like wastewater treatment plants, Combined Heat and Power incinerators, waste treatment, etc.

The concessions related to those investments are usually 20 years long Build-Operate-Transfer projects, long enough to attract the interests of Chinese entrepreneurs and speculators with no preparation in the field.

Local Governments, in charge to define and plan the PPP projects, in order to avoid those unprepared investors, resorted mainly to State-Owned companies (either at local and central level) or Listed companies.

PPP projects, by their nature, require a large amount of capital investment in the initial stage, and the PPP projects cycle is long, making it difficult for the social capital to recover the cost in a short period: a typical risk of the Public Private Partnership is that industrial and financial investors may incur in cash flow pressure[2], if not distress in some cases.

In just three-four years, a huge wave of new PPP projects were concentrated into a limited number of players, causing more than a simple cash flow pressure: between 2018 and 2019, some of those State-Owned and Listed companies went under a partial corporate restructuring, among them some market leaders such as Poten Enviro[3] and Orient Landscape[4].

Moreover, the reform of the concessions and of the Public Private Partnership has been established to contain the public debt mainly of the local Governments: the State Council issued its Opinions on Strengthening the Administration of Local Government Debt (State Council, 2014c), banning borrowing through local government financing vehicles and capping the amount of debt local governments can take on. Debt can be raised only for non-profit public project investments; for other infrastructure projects with potential cash returns, such as public utilities and transportation, the State Council encourages the use of PPPs or project-specific bonds[5].

Anyway, some local Governments were able to circumvent the reform and used PPP projects to disguise debt operations, which was not registered as such. On May 2018, Nikkei Asia[6] reported about all kind of PPP (not only for Environmental Protection) “The authorities in recent months have cancelled about 2,500 PPPs, worth around 2.39 trillion yuan ($376 billion) in aggregate, after Beijing concluded that local governments were abusing the infrastructure financing arrangement to circumvent controls on their borrowing, adding to a worrisome growth in public debt. The halted projects represent about 18% of those in the official pipeline.

[…]Chinese officials began to adopt the PPP model only in 2014. In under four years, about 14,000 projects, valued at over 20 trillion yuan, had been initiated, a staggering amount even by Chinese standards.

More than 60% of the companies involved are state-owned entities, according to analysis of a sample of 572 projects by the Ministry of Finance's China Public Private Partnerships Center. The center found that just 4% of PPP participating companies came from Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan, with another 2% coming from other countries. The balance of participants were Chinese private companies”.

From the financial point of view, China’s main solution to finance cash flow of PPP projects is Green Securitisation[7]: Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) are special kind of bond whose income payments and hence value are derived from and collateralized (or "backed") by a specified pool of underlying assets; they are believed to be the required tool for to keeping pace with scaling up of green bond issuance.

Starting from 2019-2020, major State-Owned and Listed Companies engaged in PPP projects, such as China Everbright Water[8], are issuing their first Asset-Backed Securities.

In 2019, Asset-Backed Securities represented 6% of the total Green Bonds[9].

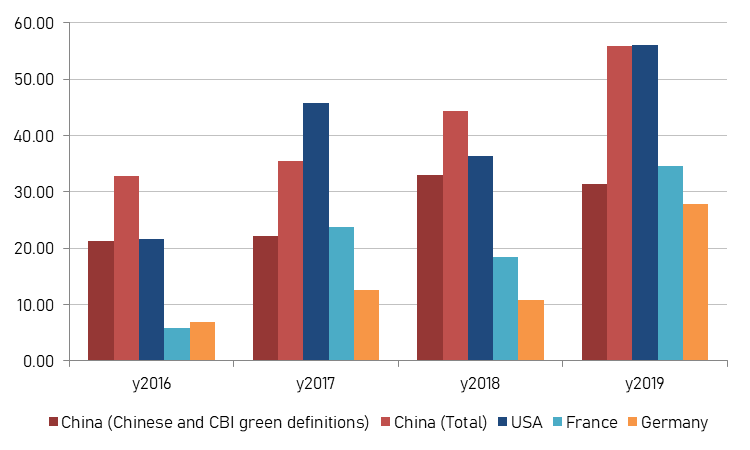

China is among the 4 leading Countries in issuing Green Bonds: between 2016 and 2019, China issued Green Bonds for a total of 168.75 billion USD.

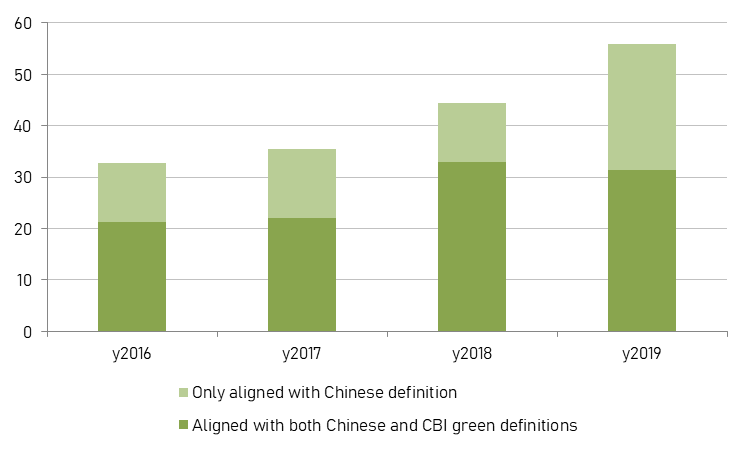

The way that China defines Green Bonds is different from international standards, because it includes also exploitation of fossil-fuels and projects that are not categorized as “Green”, “Social” or “Sustainability” by international investors: 36.2% of those 168.75 billion USD are compliant only with the Chinese domestic definition (Figure 3).

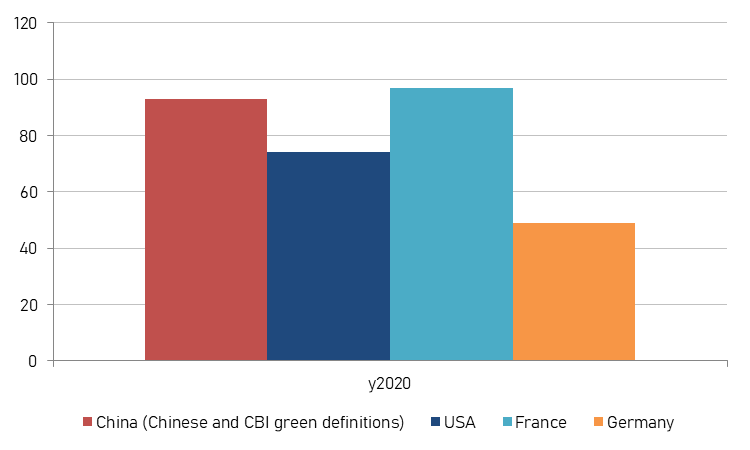

China is accelerating Green Bonds issuance, between 2016 and 2019, showing steadily increasing numbers (Figure 4), with a leap in 2020, when it became the second issuer after France, according to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) definition (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Green Bonds issued in 2020 by the 4 leading Countries, elaboration on data of Climate Bonds Initiative, value in Billion USD.

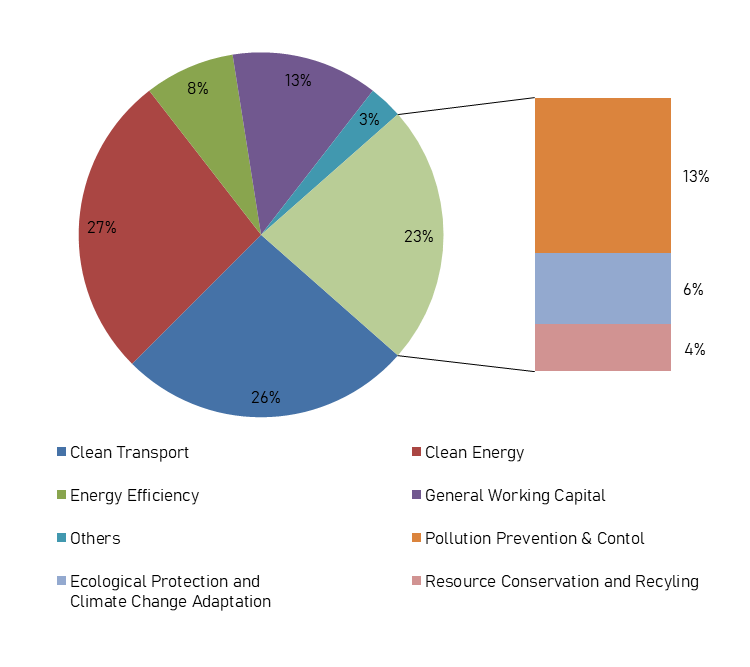

According to CBI[10], in 2019, 60% of China’s domestic market is composed of bonds with term up to 5 years and 33% have a tenor between 5 and 10 years, the first ones are issued mainly by Financial Corporates and the second ones mainly by Nonfinancial Corporates. Only 23% are issued to support project for Environmental and Ecological Protection, including Climate Change adaptation and resource Conservation and recycling (Figure 6).

However, green bonds account for less than 1% of China’s $18 trillion bond market and they still matches a tepid domestic demand, because green projects that take a long time to complete are seen as risky, so there is not enough market support[11].

In order to make Green Bonds more appealing for international investors, on 22 April 2021 China ruled out fossil fuels from eligible financing and China is working in defining a more standard classification of the projects[12].

In conclusion, while PPP projects are the main vehicle to realize the required environmental protection infrastructures, Green Bonds, including Green Securitisation, are intended to be the main tool to ensure liquidity and support cash flow, nonetheless, green bonds are not enough and PPP mechanism reached a structural limit.

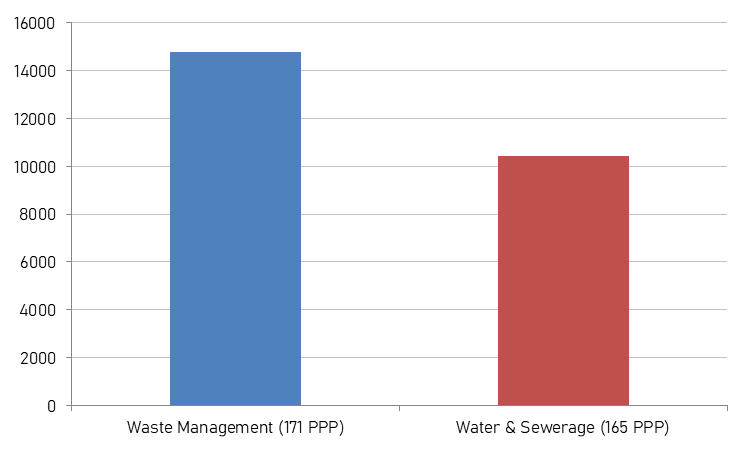

Up to 2016, World Bank monitored around 341 new PPP projects on environmental protection for a total of 25.2 billion USD, 55% in waste management and 45% in water and sewerage (Figure 7).

142 projects are sponsored by China Everbright International, for a total value of 9.6 billion USD, 16 projects are sponsored by Beijing Origin Water for a value of 1.3 billion USD, 14 projects are sponsored by CECEP Guosheng for a value of 488.15 million USD, 11 projects are sponsored by Sound Global for a value of 331.77 Million USD; out of the 5 projects sponsored by foreign companies, two are sponsored by Engie (Suez) for a value of 1.2 billion USD.

The remaining 153 projects, for a total of 12.2 billion USD, represent the 48.1% of the invested capital and each project has a different sponsor.

The concentration index in the top four companies (CR4) is 46.4%: an industry in the range 40% - 70% is to be considered on the level of oligopoly.

Even with an overabundance of financial means, a limited number of State-Owned and Listed companies can’t take on by themselves to the huge wave of required investments: designing, building and operating complex facilities, such as water treatment, waste treatment and recycling, requires availability of well trained staff, with senior experience in problem solving, since environmental protection is not an exact science and it requires a deep knowledge that comes in learning by doing.

So many PPP projects all at once require overstretching of senior staff, while new generations of middle and high ranking managers and professionals requires ten to fifteen years, including university education, to rise to the occasion: Environmental Protection Market in China is suffering skill shortage and it is in need to rise the "capacity building" of both the public utility companies and the local Governments.

Both, in fact, reacted to the lack of capacity and skill by resorting to a "one size fits all" approach, in an attempt to introduce a forced standardization of processes, but the results could only be approximate or even lead to waste of money and sunk investments, to the point that, on several occasions, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment reacted by sending inspectors to try to combat the phenomenon[13].

Such lack of skill and capacity building could be achieved in a mix of two ways:

- In the short term and middle term, by attracting a number of foreign environmental protection companies that have available capacity and experience in the industry;

- in a middle-long term, by training the staff and by letting the staff enough time to accumulate experience about problem solving. This approach may lead in making mistakes that other operators have already faced and solved, that’s why partnerships with foreign experienced environmental protection companies may be even more beneficial.

However, foreign industrial investors in PPP projects are much less welcome than financial investors in green bonds: in the aforementioned case of the 341 PPP projects monitored by World Bank, only 4.8% were those involving foreign sponsor, as well as the aforementioned article of Nikkei Asia stated that foreign only 2% of PPP participating companies were coming from abroad, out of the 572 projects monitored by the Ministry of Finance's China Public Private Partnerships Center.

The attitude towards foreign environmental protection companies is well explained in some administrative documents at province level, such as the “Chongqing Environmental Protection Industry Cluster Development Plan (2015-2020)"[14] and the "Sichuan Province Energy Conservation and Environmental Protection Equipment Industry Development Plan (2015-2020)"[15].

Those documents reveal a very clear market layout, environmental protection companies are divided into 3 tiers:

- the first tier is made of public utility companies and those State-Owned and Listed companies that act as EPC contractors in PPP projects. It’s not unusual that a company owned by a provincial Government acts as public utility company in its Province and as EPC contractor in other Provinces, they also invest in technology manufacturing, R&D in order to collect a portfolio of patents.

- The second tier is made of smaller companies, specialized in specific processes and technology, usually invested by the first tier companies; they are also called “backbone companies” and their purpose is to be the first level providers of the first tier companies.

- The third tier is made of all the other companies, including all the foreign ones. According to CAEPI (China Association of Environmental Protection Industry) the environmental protection companies in this tier are around 20,000. 90% of those companies are in the fields of prevention and control of water and air pollution and treatment and utilization of solid waste resources, only about 4% are considered large-scale companies with revenues of more than CNY400 million (~62 million USD)[16].

Domestic Second and Third Tier companies are encouraged to establish partnerships with foreign one in order to acquire “core and advanced technologies”: the designated place of the foreign companies in the Chinese market is as technology providers of second and third tier domestic companies.

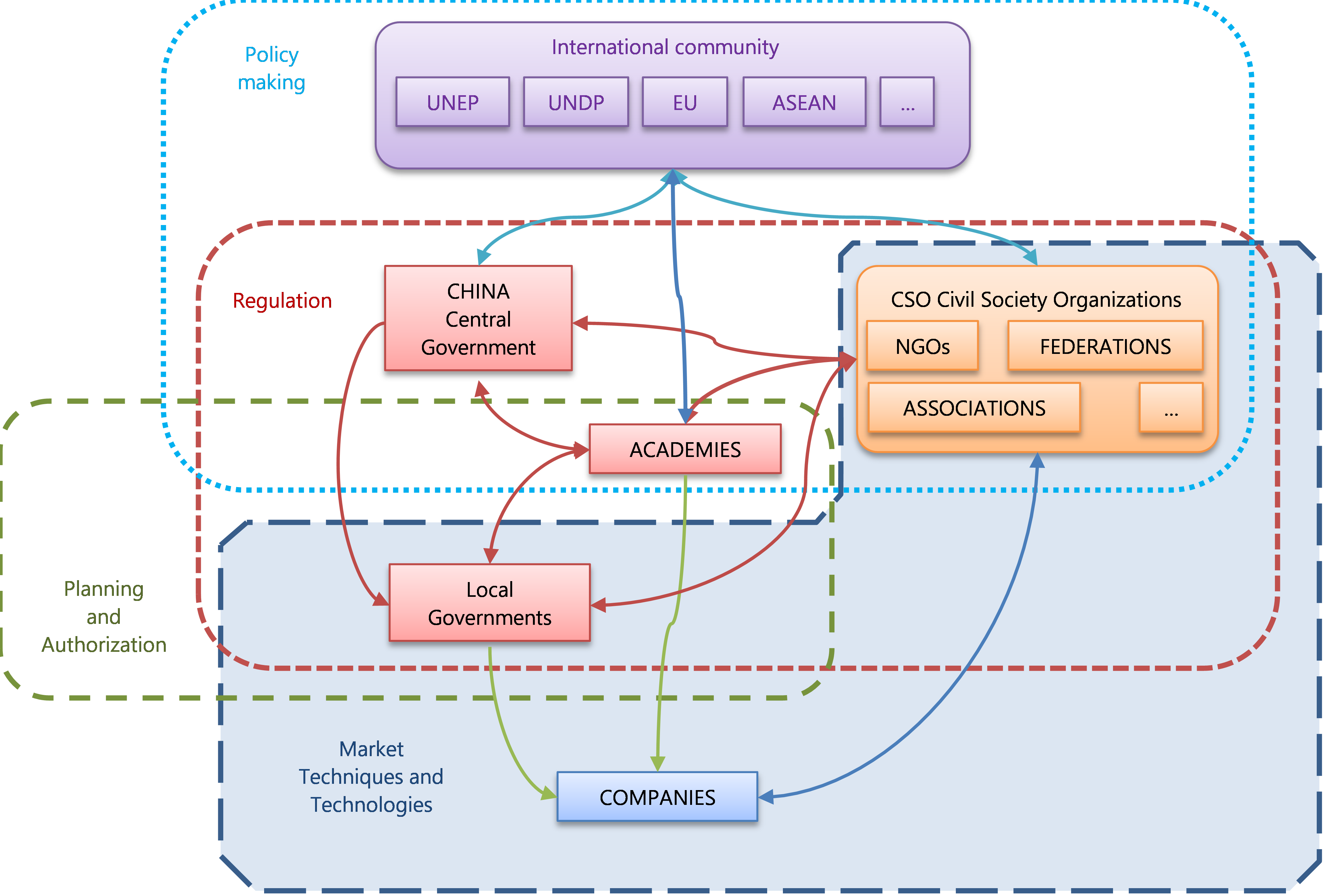

With the massive use of PPP projects and the increasing number of companies in second and third tiers, the Chinese Government also fostered the constitution of Trade Associations and Federations at national and local level, whose members are Companies and top management is composed of former public managers, reaching a complex map of market stakeholders (Figure 8).

Nonetheless, regarding foreign companies, the “National Sword” operation (the 2017 ban on importation of recyclable scrap materials), just by the name, is crystal clear political statement: environmental protection and circular economy are a domestic business.

[1] “Roadmap for China: green bond guidelines for the next stage of market growth”, April 2016, Climate Bonds Initiative and the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD)

[2] “Asset-Backed Securitization of Chinese PPP Projects”, XIAOKUAN LI, 2019, Royal Institute of Technology, Department of real estate and construction management, Stockholm, https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1335044/FULLTEXT01.pdf

[3] https://www.reuters.com/companies/603603.SS/key-developments

https://www.reuters.com/finance/stocks/603603.SS/key-developments/article/4140531

[4] https://www.reuters.com/companies/002310.SZ/key-developments

[5] “PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS IN CHINA”, 2015, International Institute for Sustainable Development, https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/public-private-partnerships-china.pdf

[6] “China must put the 'private' into PPP”, Michel Brekelmans, 17 May 2018, https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/China-must-put-the-private-into-PPP2

[7] "Roadmap for China: Using green securitisation, tax incentives and credit enhancements to scale green bonds", Climate Bond Initiative, 2016, https://www.climatebonds.net/files/files/CBI-IISD-Paper3-Final-01B_A4.pdf

[8] 17 June 2020, https://www1.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/sehk/2020/0617/2020061700940.pdf

[9] "China Green Bond Market, 2019 research report", Climate Bonds Initiative, https://www.climatebonds.net/resources/reports/china-green-bond-market-2019-research-report

[10] Climate Bonds Initiative, Op. Cit.

[11] "China leads global green-bond sales boom but faces headwinds", 1 April 2021, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-bond-green-idUSKBN2BO4FP

[12] "Clarity on green bond issuers underlined", 23 April 2021, China Daily, http://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202104/23/WS60821f0aa31024ad0bab9c58.html

[13] "Ministry: No tolerance for rigid approaches to local pollution", China Daily, 20 September 2019, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201909/20/WS5d84971ca310cf3e3556ca79.html

[14] "重庆市环保产业集群发展规划(2015—2020年)", "Chongqing Environmental Protection Industry Cluster Development Plan (2015-2020)", http://www.cq.gov.cn/zwgk/zfxxgkml/szfwj/qtgw/201504/t20150406_8613837.html

[15] "四川省节能环保装备产业发展规划(2015—2020年)","Sichuan Province Energy Conservation and Environmental Protection Equipment Industry Development Plan (2015-2020)", https://huanbao.bjx.com.cn/news/20160630/746995-5.shtml

[16] "Leveraging Private Sector Participation to Boost Environmental Protection in the People’s Republic of China", Asian Development Bank, April 2020, https://www.adb.org/publications/private-sector-environmental-protection-prc